Introduction

I’ve been reading some things that have gotten me suspicious they were written by AI. I got so suspicious that I thought a policy-based academic article had been written by AI—but the publication came out in 2019! Before I go further, let me say this feeling…this suspicion…makes me frustrated. I don’t like it. It makes me feel paranoid.

What was pinging me to think the article was written by AI? It was this sentence:

“AI can be classified into analytical, human-inspired, and humanized AI depending on the types of intelligence it exhibits (cognitive, emotional, and social intelligence) or into Artificial Narrow, General, and Super Intelligence by its evolutionary stage.”

When I read this sentence, I say to myself, “Oh that has an AI feel.” It was the multiple listings as well as the repeated use of the conjunction “and.” My reaction to lists—cataloguing—is now to wonder why those words or phrases are being used over a single precise word. In the above sentence, I reacted to the following two lists:

List 1:

analytical,

human-inspired, and

humanized

List 2:

cognitive,

emotional, and

social intelligence

The words in List 1 are, at best, fuzzy in their distinctions. In List 2 the differences are clearer but I’m not sure how to connect List 1 to List 2, though the sentence implies clarity about the connection. In this example, there is even a third list above but that appears to me to be a technical categorization that makes a bit more sense, but only because I’m familiar with the terms (Artificial Narrow, General, and Super Intelligence).

I’m more concerned with my own concern. I’m concerned with the disposition that it’s making me adopt. The sentence was clearly not written by AI; the technology wasn’t around in 2019. What got my “AI radar” up was how the sentence made sense the first time I read it but, after thinking about it, the sentence was so complex that it overloaded my brain. In fact, it has 9 concepts in a 35-word sentence. In other words, there are so many concepts packed into a single sentence that it’s hard to keep track of them. A lot of academic writing is like this. Same with public policy documents or legal briefs.

I’m concerned with the consequences of my own disposition. It’s affecting my personal cognition as well as the way I read and write now. For example, in the previous paragraph, I originally wrote this sentence, “A lot of academic writing is like this” as “A lot of academic, policy, and legal writing is like this.” I had created a list. I edited the sentence to sound less like AI writing.

Am I editing my writing to sound less like AI? To sound less academic? Does avoiding lists nowadays make me sound less precise? I wanted to check myself here, so I tried something with ChatGPT. The following was written by ChatGPT from the prompt “Write an arugment in pargraph form that AI wll not take over teh world” (I typed this into the bot, misspellings included).

“AI will not take over the world because it lacks independent agency, intrinsic motivation, and the complex, adaptable reasoning that human beings possess. AI systems, including the most advanced machine learning models, operate within the parameters set by their human creators, relying on data inputs, predefined objectives, and programmed constraints. Unlike humans, AI does not have desires, intentions, or the ability to form long-term goals beyond what it has been trained to optimize. Additionally, AI is fundamentally dependent on infrastructure—electricity, hardware, and human oversight—all of which limit its ability to function autonomously. Even in scenarios where AI is deployed for decision-making, it remains subject to human intervention, legal restrictions, and ethical considerations that curb its unchecked influence. Furthermore, AI models are prone to biases, errors, and adversarial vulnerabilities, making them unreliable as independent actors. The idea of AI "taking over" often stems from science fiction rather than reality, as it assumes AI can transcend its current limitations and evolve into an autonomous force with its own will—something that neither current technology nor foreseeable advancements support. Instead of fearing AI domination, the real challenge lies in ensuring responsible development, governance, and ethical implementation to maximize its benefits while mitigating risks.”

Let’s break this AI paragraph down by sentence:

1) AI will not take over the world because it lacks independent agency, intrinsic motivation, and the complex, adaptable reasoning that human beings possess.

2) AI systems, including the most advanced machine learning models, operate within the parameters set by their human creators, relying on data inputs, predefined objectives, and programmed constraints.

3) Unlike humans, AI does not have desires, intentions, or the ability to form long-term goals beyond what it has been trained to optimize.

4) Additionally, AI is fundamentally dependent on infrastructure—electricity, hardware, and human oversight—all of which limit its ability to function autonomously.

5) Even in scenarios where AI is deployed for decision-making, it remains subject to human intervention, legal restrictions, and ethical considerations that curb its unchecked influence.

6) Furthermore, AI models are prone to biases, errors, and adversarial vulnerabilities, making them unreliable as independent actors.

7) The idea of AI "taking over" often stems from science fiction rather than reality, as it assumes AI can transcend its current limitations and evolve into an autonomous force with its own will—something that neither current technology nor foreseeable advancements support.

8) Instead of fearing AI domination, the real challenge lies in ensuring responsible development, governance, and ethical implementation to maximize its benefits while mitigating risks.”

It’s not a bad paragraph. It all seems more-or-less correct. But stylistically, it’s bizarre.

Humans don’t write like this.

There is not a single simple sentence. Every sentence has a comma. Every sentence has multiple listings with arduously complex phrases. In seven of the eight sentences, there are lists of 3+ concepts/phrases/words (I did it again!—I used backslashes here to avoid sounding like AI).

I’m reminded of an anecdote from an interview I did with a self-driving car expert. She told me that self-driving cars don’t brake like a human being. They stop too abruptly without notice. This causes them to get into more accidents with human drivers, even though the human driver is at fault due to laws about rear-ending.

The AI-written paragraph doesn’t seem to behave like a human. Human writing has a certain variety. It’s almost ineffable. Linguistics attributes this to the concept of “bursts” in writing. Humans think as they write. As they stitch together ideas, they don’t think in uniform patterns, which results in uneven sentences. These “bursts” make the sentences, hopefully, more interesting to read. It means, too, that sentences aren’t always dense.

It’s these bursts that I typically look for in student writing. That’s where I can see the idea generation occurring. I try to find sentences that—though they may be rough—are kernels of interesting or promising ideas. But AI writing doesn’t have these “bursts.” As a writing teacher, as I’ve written before, I struggle to help students revise AI generated text because there aren’t promising ideas in AI sentences. AI sentences, rather, are banal because these technologies select from the middle of the statistical distribution. These bots write in distinctly average ways. They’re programmed to be average. They’re programmed without quirks. A colleague texted me a few weeks ago saying that AI writing has a “haunting uniform polish.” He called it disturbing. I call it designer syntax without any content.

Lists, hypotaxis, and “and” clauses: Why does AI like these things?

(Oh yes! I see the irony of the subheader above but I can’t totally avoid lists.)

So what does AI writing look like? What is the designer syntax it loves?

First, AI writing uses lists because it doesn’t know what word to use. I’m serious here. The math is important because there is no understanding of meaning from the AI tool. It’s raw statistical power—and lest you think I’m a technophobe or luddite, I find this power impressive. That OpenAI’s ChatGPT or Google’s Gemini are so often correct means that the underlying mathematics is at least approximating some form of learning. Remarkable.

Let’s take a look at why these tools use lists. The sentence below is an example from the AI paragraph:

Furthermore, AI models are prone to biases, errors, and adversarial vulnerabilities, making them unreliable as independent actors

The list here is: (1) biases, (2) errors, and (3) adversarial vulnerabilities. These are all weaknesses of AI models, nothing original here. These weaknesses aren’t unique to AI models; they are criticisms of any model. They’re criticisms of any piece of software. Perhaps most importantly, they are criticisms of nearly any technologies or tools humans have ever created. They’re perfect words for a machine to use when it doesn’t understand how to make an argument. They’re perfectly vague such that they prevent any criticism from being lodged. By writing a sentence so vague that it encompasses any claim over reality, AI writing approximates a correct answer.

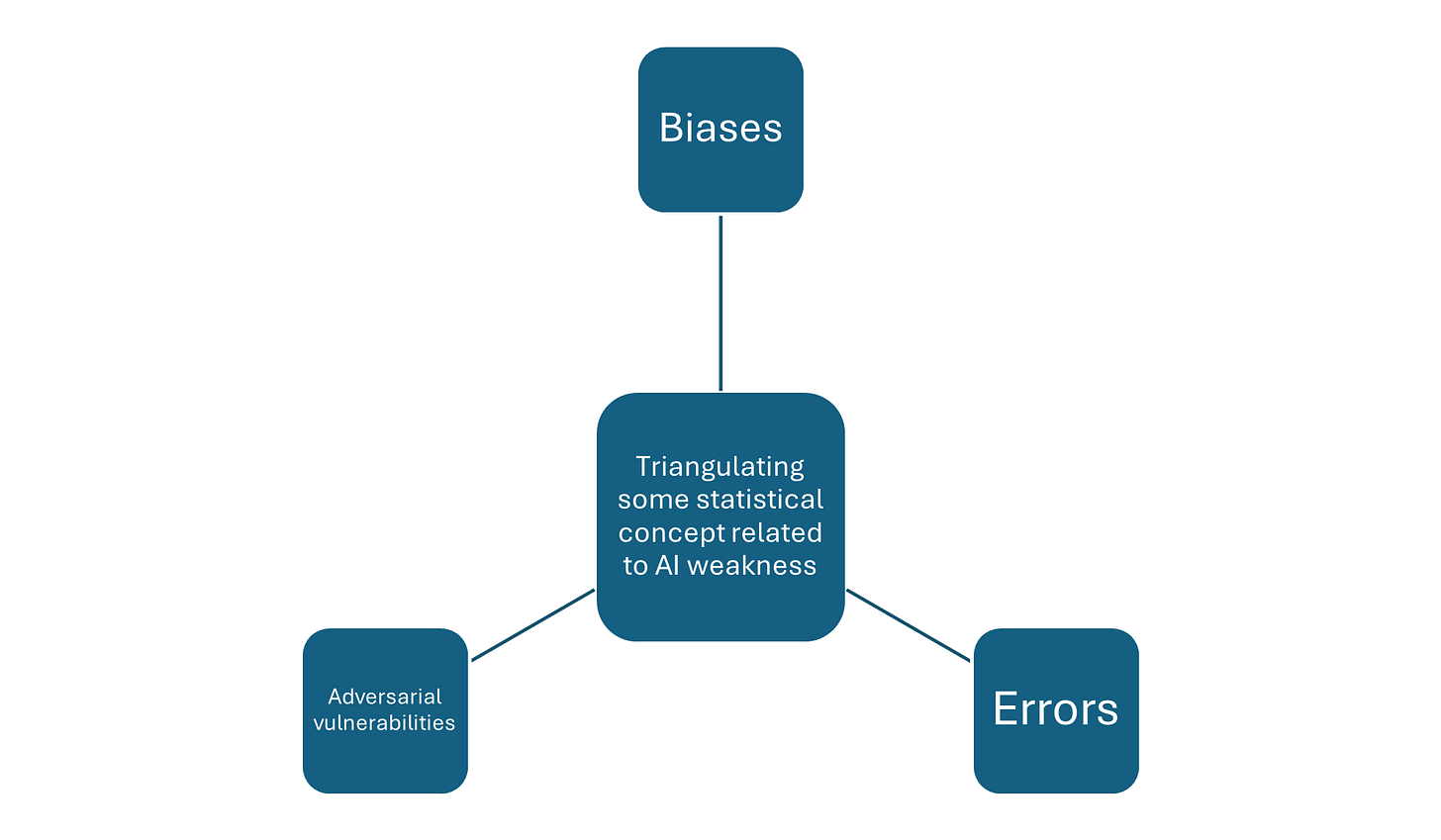

It’s curious why the lists are so prevalent by default. One can instruct these tools to avoid lists, which reduces the frequency of lists but they’re still almost always present. The answer lies in the lack of understanding going on under the hood. Precisely because they use prediction and not understanding, AI needs to approximate meaning—again, prediction with enough data can, as these models demonstrate, get one pretty far. Listing and cataloguing triangulate meaning for something that it is trying to calculate. The image below tries to visualize what I mean.

The AI model turns these concepts in the figure above into numbers, which I’m just making up in the figure below. I’m handwaving the math here.

I’m convinced this is why lists are prominent in AI writing. If the AI tools use multiple words or phrases, they can better calculate a string of text that appears correct to the human user.

Another reason is that a lot of the data used to train these systems uses lists. But why would the data deploy lists so frequently? Who writes in lists so frequently? I’ll get to that in a little bit.

The second feature of AI writing: it loves hypotaxis. Stanley Fish, in How to Write a Sentence (2011), discusses hypotaxis as follows:

“The technical term for the accomplishment of the subordinating style is hypotaxis, defined by Richard Lanham as “an arrangement of clauses or phrases in a dependent or subordinate relationship” (A Handlist of Rhetorical Terms, 1991). Hypotaxis, Lanham explains, “lets us know how things rank, what derives from what” (Analyzing Prose, 1993). (The fact that “hypotaxis” is a Greek word tells you how old the classification of styles is.) The James sentence is a modest version of the style. More elaborate versions can go on forever, piling up clauses and suspending completion in a way that creates a desire for completion and an incredible force when completion finally occurs.” (p. 51)

Fish valorizes hypotaxis. Complex sentence structure with subordinating clauses are, for Fish, a good thing. I imagine that Fish likes long sentences because he enjoys language. Hypotaxis sounds better to him, more elegant. He likes fancy sentences.

But if you go back to the AI paragraph, I’ll note that the hypotaxis is not in service to any purpose. Nothing pops with “incredible force” as Fish might hope. Rather, it’s these clauses with lists that make me, as a reader, think, “There is nothing there there.” The machine has no idea what it’s doing. AI writes fancy sentences without any knowledge of those sentences.

It isn’t making arguments so much as predicting words or clauses that it will approximate an argument.

To approximate an argument, AI writing bots use the word “and” instead of argumentative language. These chatbots avoid words such as:

Therefore

Thereby

Accordingly

Consequently

Following this line of reasoning

AI writing rarely uses these words because it’s only using statistics. There is no understanding going on here.

Instead, AI writing tools use “and” to chain together multiple ideas to be statistically correct. The statistical procedure is why AI sentences use so many lists and is so looooong. When AI writing is trained to sound fancy, it obscures the meaning in a cloak of complexity that sounds right initially. By using so many lists and hypotaxis, AI writing exhausts the reader into submission. It forces the reader to acquiesce that the sentence is probably, mostly, fairly, somewhat correct. Approximately correct.

And yet. But wait.

I have a sneaking suspicion…I’ve encountered this problem before. Long before AI, I encountered problems with lists. I’ve already butted up against complex sentences. I’ve been ground down by vague claims. I know this feeling, this mental tyranny of arduous sentences.

Sounding fancy

I’ve encountered this problem with academic jargon. If you flip to any page in Derrida’s Of Grammatology, you’ll find hypotaxis sprayed about. In 1999, Judith Butler won an award for the worst academic sentence:

“The move from a structuralist account in which capital is understood to structure social relations in relatively homologous ways to a view of hegemony in which power relations are subject to repetition, convergence, and rearticulation brought the question of temporality into the thinking of structure, and marked a shift from a form of Althusserian theory that takes structural totalities as theoretical objects to one in which the insights into the contingent possibility of structure inaugurate a renewed conception of hegemony as bound up with the contingent sites and strategies of the rearticulation of power.”

Homi K. Bhabha won runner-up:

“If, for a while, the ruse of desire is calculable for the uses of discipline soon the repetition of guilt, justification, pseudo-scientific theories, superstition, spurious authorities, and classifications can be seen as the desperate effort to 'normalise' formally the disturbance of a discourse of splitting that violates the rational, enlightened claims of its enunciatory modality.”

In both sentences, the listings and hypotaxis of academic writing are laid bare. I won’t break them down into lists, so as not to bore you, my faithful reader. (I respect you for reading this far, by the way. I appreciate that.) Both authors are notorious for dense, obscure academic writing. They’re also award-winning authors, canonical in their respective fields of study.

To be clear, I don’t think the above sentences are entirely nonsense.

I do think, however, that sentences like the ones above use overly complex sentence structure, complicated syntax, and vocabulary words designed to impress readers more than communicate to readers. The multi-syllable words are performances. (In fact, I had originally used “polysyllabic” in the previous sentence but decided to replace it with “multi-syllable” to avoid performing myself.) Put simply: The sentences sound fancy. But just because something sounds fancy doesn’t make it meaningful. Just because something sounds obscure doesn’t mean it makes sense.

These kinds of sentences make me question myself. Even when reading Butler and Bhabha in a genuine, honest manner, I’m not sure what those sentences mean. I’m convinced that Derrida was playing a nonsense joke on American academics with deconstruction—in fact, in an interview with Gary Olson, Derrida even admitted as much. In many ways, I think these types of sentences are meant to be vague so as to be suggestive.

Suggestive sentences can be interpreted in multiple ways, thereby increasing their opportunities to be cited by scholars. If a sentence is suggestive while remaining ambiguous, then future academics can use it for their own work. It’s the quoting game of modern academic scholarship. A game that is full of citation chains where the more citations in the chain, the better. Lest you think I’m innocent: a reviewer once said my academic writing is full of “overstuffed parentheticals.” The reviewer was correct.

The fanciness of AI writing is similar: vague, suggestive. The impenetrable and obscure meaning feels intentional. Now perhaps there are different reasons at play. The prose of AI writing has a decidedly more business, transactional feel to it. Rather than using vocabulary intended to impress at a cocktail party, AI writing uses words that seem appropriate for a Silicon Valley press release.

Here’s the difference: good, dense academic writing appears designed to be read multiple times. To be sat with. Butler and Bhabha want you to wrestle with their words, puzzling through them. I’m even convinced they would like readers to argue with their ideas (and cite them, of course). True academic disagreement is a sincere form of flattery.

On the other hand, AI writing is designed to never be read again. It’s fast-food writing. Order it, skim it, toss it into the garbage can. It feels nice on first chew. It feels correct on a skim. But if you read it twice, you’d wonder if it had any real meaning at all. If you chew it multiple times, you begin to taste the plastic. The fancy packaging can’t hide the empty calories.

The fast-food nature of AI writing is what everyone seems excited about. The media and AI corporations want to sell us disposable writing that means nothing. The end product of the drive-by internet, where people endlessly scroll on their feeds, is writing meant to be skimmed. You’re not supposed to read that article on social media, just glean a few keywords to get a feel for the writing. You aren’t supposed to think about it. After all, how many times have you shared an article without reading it?

If no one is reading, and we are only skimming, fast-food writing makes sense. No one wants to take the time to carefully write because no one takes the time to carefully read.

On being a genuine reader

I have trouble discerning between complexity of thought (academic writing) and complexity of sentences (AI writing). I have trouble finding the meaning in both, though for different reasons. I have begun practicing being a better discerner. I have started slowing myself down in all facets of my life.

Discernment is the future of being a good writer (and teaching writing, my chosen vocation). Perhaps this has always been the goal: to write in a discerning way. To teach the craft of writing in a slow, deliberate way. And, ideally, to teach students to be discerning thinkers.

I teach writing at the college level. My sense is that my current students—who came of age in the COVID lockdowns, an era of distance learning—have never had a genuine reader. I worry about this with my own children. I worry about them learning that AI writing is good writing, internalizing those performative features. I need to provide them with an honest, engaged reader. Perhaps it has to be me: someone engaged with their ideas and craft. If I don’t engage with their craft and their ideas, who will?

Corporate social media only provides them with surface engagement, a male gaze of branded authenticity. Successful online writing is empty ad populum, which is a fallacy that a correct argument is one that appeals to the crowd. But did anyone read it? Few people will ever return to online content. After it’s posted, online content is chewed and digested by users, promptly forgotten. Users move on. Readers move on. Writers move on.

The tyranny of AI writing is a broader tyranny: of being forgotten. If we mediate our writing through AI, we mediate our relationships through AI. We risk losing the very reason for why we write: To communicate, with others.

Conclusion: Some solutions

As writers, we don’t talk much about the nitty gritty of the process of writing: of how much time it takes us to write, how difficult it is to write, and the frustrating agony of crafting sentences. The biggest secret in all of college and education is that writing well is the hardest subject to learn. It’s not math. It’s not engineering. There is no single right answer when writing, but still many wrong answers.

When you finally write successfully, it is an outstanding accomplishment.

Part of what makes successful writing so gratifying is precisely the struggle to get there. It’s a struggle to think about word choice. I want to avoid listings not only to avoid sounding like AI but also to be diligent about my word choice. My words shall be intentional. In my previous academic work, if I couldn’t think of the exact word or phrase, I used a list. If I listed enough ideas, I was giving myself cover. It was a way to spray down the sentence to inoculate it against criticism. It was like spraying down a field of corn to keep away the bugs.

I need slow writing. Slow writing crafts, polishes, deliberates. It takes time and patience to do this. It requires having a genuine reader, one who not only believes in my writing but also wants to make that writing better.

Such is the problem with both AI and academic hypotaxis. It doesn’t ever really “pop.” As Fish might wonder, it rarely creates “an incredible force when completion finally occurs.” The entire point of well-orchestrated hypotaxis, possibly the entire point of writing, is to make the reader feel something, if only for a moment, if only so that we feel a human wrote it, making us burst.

What's funny about Butler’s sentence to me is, all those “X which Y” constructions? If they were writing mathematics, I'd expect there to have been some definitions made, to chunk those concepts. Then they could be referring to what these chunked concepts (themselves probably chunking some other chunked concepts) were relating to.

I'm increasingly thinking some of the most vital skills for humans in this era are philosophy (what is truth, and how do we know), journalism (what is said is true, and who said so), and mathematics (what is true logically if the only ground truths are the definitions you choose).

Really insightful (and helpful) piece, thank you! I have been experimenting with various approaches to incorporating LLMs into my writing process to help move past various blocks, and one thing I have noticed is that given enough pieces to work with (e.g. notes, quotes, memos), LLMs can produce something akin to what I think I would write. Or at least so I think on first read -- then I sit with it and realize that I was just projecting the meaning I wanted the writing to have onto well-structured sentences. Probing them more intentionally, those sentences end up being fairly devoid of meaning, or at least of the punch of an idea. So while it doesn't work for producing usable text (which, to clarify, is not something I would want it to do), it does provide an object for me to project the meaning I want to make onto, and I can then make progressive modifications to that object to actually get at that meaning.

I'm sure this leads me to a very different process of writing that loses something from a non-LLM-infused writing style, but I do think it's an interesting practice to try to hone (especially for the time being, where it helps me get through the writing that I need to produce while I continue working on my writing anxiety). And I think your insights on what makes AI writing so vapid will be very helpful in this honing process!